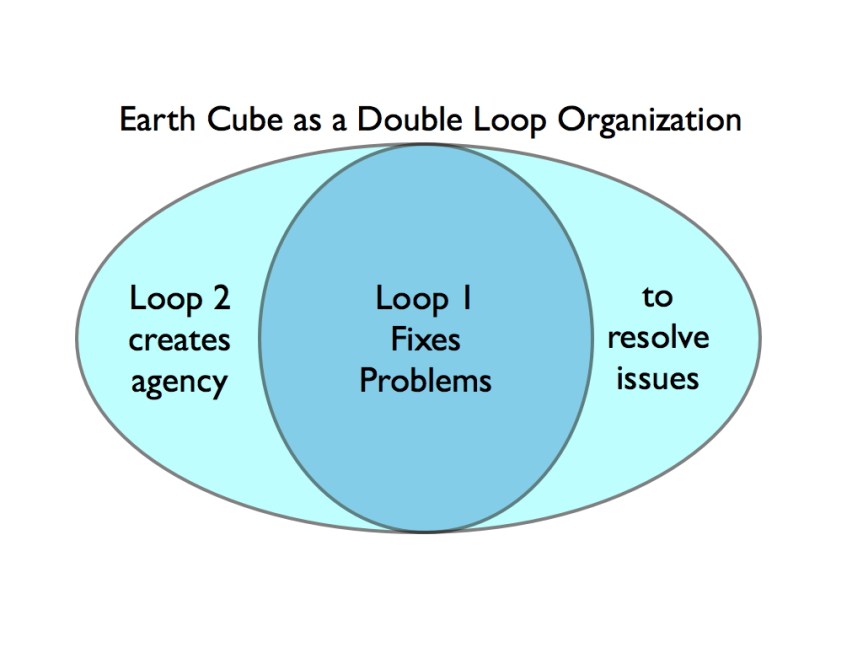

I’ve been listening in on the opening discussions at the Earth Cube governance meeting, and I’m impressed by the level of passion and amount of expertise at the table. I’m also interested in how the conversations seem to whiplash from notions of democracy and community to ideas for data standards. People have come to the table with divergent notions of what governance means, although they are also aware that governance can mean both democracy and data standards. I would like to argue that they are looking at the same organization, but they are each describing only one of the governance “loops” that will be needed for Earth Cube.

Take a look at this Keynote talk by Clay Shirky (DrupalCon 2011)

http://archive.org/details/drupalconchi_day2_keynote_clay_shirky

about 45 minutes into the video Clay is talking about organizations that not only fix problems, but that simultaneously can solve the larger issues that created the problems. In these “double-loop” organizations, the members agree to governance rules that solve common problems for their interactions (e.g., data sharing). At the same time, they agree to own these rules, that is, to govern their governance system. And so, when someone talks about building community, protecting expressive capabilities, voting, officers, and working consensus, constitution and bylaws, vision statements and goals: they are approaching Earth Cube governance from the second loop. This is where the members of Earth Cube agree to be its owners. And when someone talks about data sharing policies (enforcement, compliance, standards, etc.) for Earth Cube, they are also bringing to the table issues integral to governance. These are the activities, the goals, and the outcomes of Earth Cube as a distributed/virtual organization.

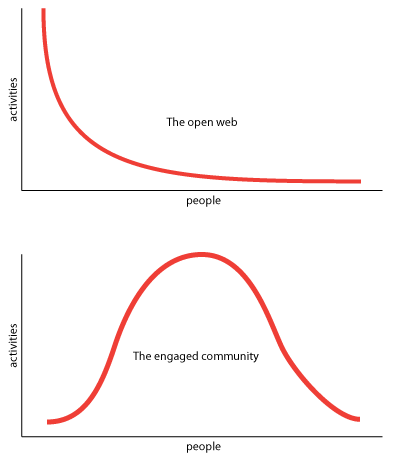

First loop governance fixes problems for the Earth Cube member community. Second loop governance creates what sociologists call “agency.” This agency is the ability/capability to govern how the community will fix its problems. Does there need to be a committee? Who gets to be on the committee? Who is involved in a decision? Who do you talk to if you feel your voice has not been heard? Second-loop governance is responsible to answer all of these questions. In a typical NSF project, this is called “management.” PI and Co-PIs are charged to create and implement an effective management plan. But who should create and implement an effective second-loop governance plan? The current vision for Earth Cube puts the community into this role. Members of the community are stepping up to guide this process. But a much larger community-wide conversation will need to happen before any second-loop governance plan can be implemented.

What about first-loop governance planning? When should this happen, and how? Initial discussions about the scope of the problems to be fixed and the solution spaces for these fixes will help articulate the amount of (loop-one) governance activities needed to effect the fixes. The model that emerges will guide the second-loop governance planners to better solutions for their level of governance. For example, if community buy-in to a strict set of data standards is needed, then the second-loop governance effort will need to plan to build a strong community. If the main requirement is better communication, then a much weaker community will suffice. But again, these discussions will need to be revisited after the second-loop governance effort is agreed to by the members. So the governance boot-strapping process will resonate between the two loops until the initial governance plan is accepted by the Earth Cube members. At that point, the second-loop governance is empowered to address new fixes, and to fix itself whenever this is needed.

A good example of this can be found in the history of the ESIP Federation. The Federation spent more than two years, and included direct participation by several dozen members before it finalized its constitution and bylaws (the main second-loop outcome). When the final vote was taken, and these documents were accepted by consensus, then the various committees, and emergent working groups and thematic “clusters” were supported to begin to fix problems faced by Federation members: data interoperability and stewardship being chief among these.

Building a governance model for Earth Cube will require looking into both loops: the first loop describes a number of fixes planned to address common problems (mainly around data use and sharing), while the second loop describes how the Earth Cube community can acquire ownership for the decision processes to determine which fixes are most important, and how to engage the broader community in their implementation.