“What would happen, for instance, if the university were to let go of the notion of prestige and of the competition that creates it in order to better align its personnel and other processes with its deepest values? Could those institutions begin, individually and collectively, by rejecting the absurdly metrics-focused line they’ve been cudgeled into by the accrediting bodies that oversee them?” (Fitzpatrick 2019).

PLEASE NOTE: This is a draft of a bit of the Open Scientist Handbook. There are references/links to other parts of this work-in-progress that do not link here in this blog. Sorry. But you can also see what the Handbook will be offering soon.

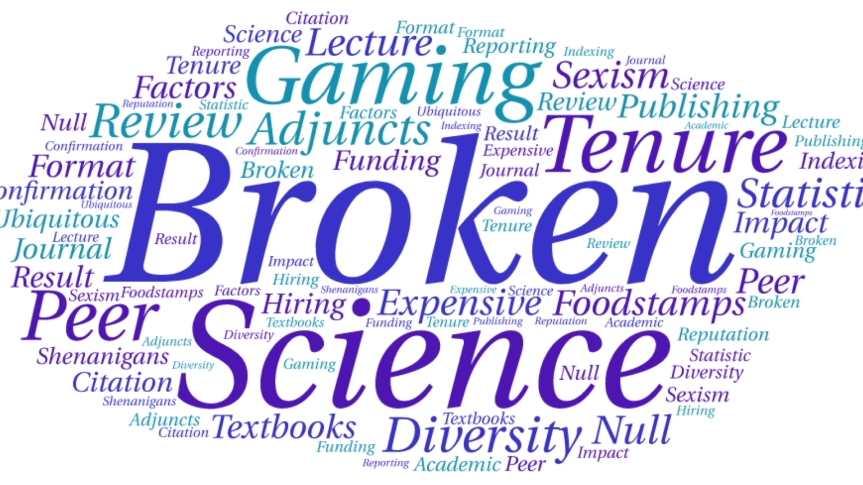

Right now, the academy finds itself in the state where failed academy institutions need to move beyond wondering how it all went so wrong, and start answering questions about their toxic cultures:

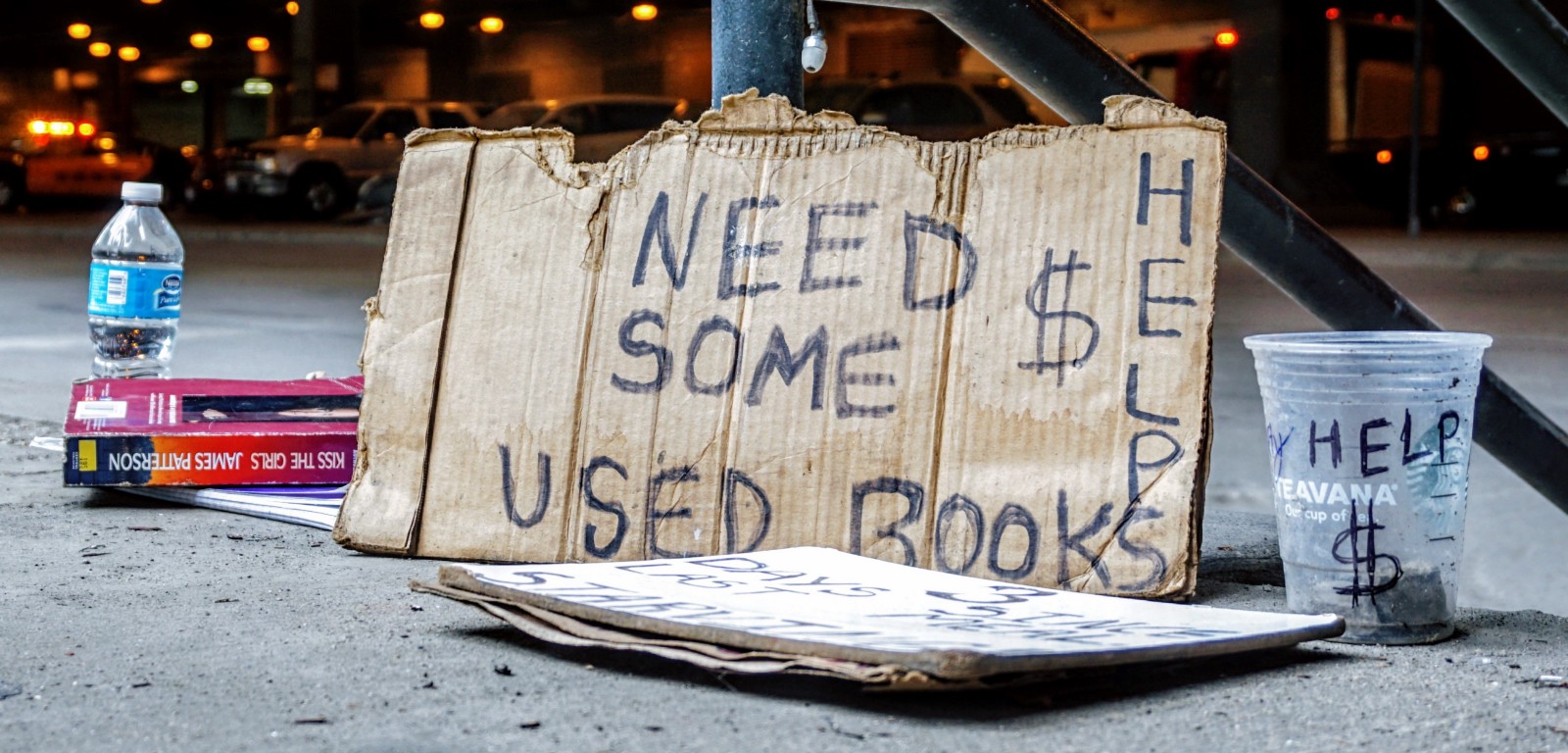

· How did university teaching become a miasma of grossly underpaid adjuncts, soft-money science staff, and administrative bloat?

· Why does doing research mean spending four months of every year writing grant proposals for programs that have an 18% success rate?

· How come hyper-competition is allowed to dominate what should, instead, be a hyper-cooperative endeavor? It’s science, not boxing.

· When did higher education become a ponzi scheme for the financial sector: where government spending over the next decade will be dwarfed by the trillions in additional student debt owed to big banks (This is a USA-centric condition)? Students should not have to become servants indentured to the financial sector of the global economy just to finish their education.

· How did we arrive at an academy where sexism is so pervasive that a large percentage of women simply leave instead of facing a lifetime of symbolic violence and professional hostility? Karen Kelski (2019) created an open Google Doc (Accessed May 13, 2019) where academics can self-report incidents of sexual harassment. More than two-thousand entries later, it is a testament to the current toxic situation in the academy.

Culture repair

Three underlying, systemic conditions that are intrinsically toxic, and which challenge other cultural practices in the academy, are well described by Yochai Benkler’s (2016) discussion of “dimensions of tension;” (Accessed August 7, 2020):

“The first [tension] is the concern with the power of hierarchy; the power within an organization to be controlling…

…A second is the concern with the power of property… [T]he problem is, of course, that property is always an organization force for oligarchy; the re-creation of power around who owns it…

And the third… is the tyranny of of the margin. The need to constantly compete in the market and find yourself in a context where you have to compete, you have to survive, you have to return returns-on-investment; and this ends up postponing the ethical commitment, because you can’t live with it.…”

So this tyranny of the margin is a real constraint that we have to find a way how to break out of.”

These three tensions are addressed by open science efforts through cultural practices that reassert core science norms: 1) fierce equality, which subverts hierarchy (Fierce Equality) (See also: Shaming the Giants); 2) Demand sharing, which opens up the scholarly gift economy (Demand Sharing) (See also: Scholarly Commons and Against Patents in the Academy), and; 3) Kindness, Culture, and Caring: creating cures for the neoliberal academy (See also: The Joy of Discovery, and the Love of Science, and The practical wisdom in doing science).

The sources for the toxic damage to cultures within the academy are multiple and their impacts global. Almost any organizational culture will go toxic if simply ignored; cultures in the academy have also been warped through intentions. One noticeable result is an old nemesis: jerks in charge, or just in the room. Bad actors in the academy may rely on status quo organizational norms and rules to support their behaviors. An non-reflexive, internally-conflicted cultural milieu gives them cover for their self-promotion. They can become powerful adversaries to culture change. This condition is so common, it has its own chapter in the Handbook: Open Science: the Need for a Zero-Asshole Zone.

Since toxic culture often supports and even applauds bad behaviors (centered around self-promotion and a lack of empathy), toxic organizations actually grow jerks (by allowing jerkish behaviors) internally over time. These assholes-of-convenience may be happier when the organizational culture becomes post-toxic. Authentic bad actors bring their own more durable personality problems to the table.

Jerks are also what Grant (2013) calls “takers.” Takers gobble up resources without contributing their share: “Takers have a distinctive signature: they like to get more than they give. They tilt reciprocity in their own favor, putting their own interests ahead of others’ needs. Takers believe that the world is a competitive, dog-eat-dog place. They feel that to succeed, they need to be better than others. To prove their competence, they self-promote and make sure they get plenty of credit for their efforts.”

Takers are easy to spot in asynchronous internet discussions; they offer little and demand much. Once you are certain that these people are bad actors they might get added to your own memory/list of toxic weak-tie associates, and can be avoided (delisted, blocked, etc.), and others can be warned about them. Gossip within the academy can offer a low-cost corrective to bad actors (either confirming other’s perceptions, or creating back-channel opportunities for rethinking one’s own evaluation of the “bad actor” (See: Feinberg et al. 2012).

Of course, not all scientists who are opposed to organizational change are bad actors. They may simply see the current system as having worked well for them, and hold the opinion that change might not lead to a better working situation. They might prefer their current situation, however toxic, over one that is more experimental, as all new cultural endeavors need to be. Benkler’s observation about “postponing the ethical commitment” can be evidenced by a consequent deluge of bullshit in the academy.

On becoming a scientist: escape from bullshit

“A scientist who is not concerned with the reproducibility of their experiment is quite simply, and somewhat paradigmatically, a bullshitter” (Frankfurt 2009).

When a scientist steps up to play the infinite game (Open Science and the Infinite Game) with her chosen object of study, there is no space, no incentive, no possible reward, for inauthentic actions. Rigor, transparency, insight, diligence: these are all marks of a congruent mind bound to the mystery it must resolve. This is not to say that scientists are necessarily saints. But rather, that the part of them that is most integral to their research must be congruent in the effort. Everything else is bullshit.

Under the logic of neo-liberal economics, where conflicts of interest intercept science practice, some scientists will cheat on the truth. When a scientist, or team of scientists, cannot own up to their failure, then; “the lack of a variety of knowledge sufficient to know what a truth might entail means that the whole enterprise becomes a project of bullshit…” (Frankfurt 2009). One of the goals of open science is to remove as many conflicts of interest as possible. Just as open science organizations need to be assole-free zones, they must also strive to become bullshit-free research endeavors.

There are other sources of baloney in the academy, mainly from sloppy analysis, poor visualization, and lazy, biased thinking. Calling Bullshit, a class at the University of Washington (Accessed April 14, 2019) spends a whole term examining various aspects of this. Kathryn Schultz notes: “confirmation bias is entirely passive: we simply fail to look for any information that could contradict our beliefs. The sixteenth-century scientist, philosopher, and statesman Francis Bacon called this failure ‘the greatest impediment and aberration of the human understanding,’ and it’s easy to see why. As we know, only the black swans can tell us anything definitive about our beliefs — and yet, we persistently fail to seek them out” (Schulz 2011). Scientists task themselves to develop a deep, reflexive awareness of their own knowledge:

“[W]hat, then, distinguishes those who are capable of reasoning scientifically from those who are not?… [I]n order to separate theory from evidence, one must also be able to reflect on the theory as an object of one’s thinking (metacognition). To coordinate and change theory to fit new and especially disconfirming evidence one must be able to stand back from one’s ideas and see them as things that can and should be tested” (Feist 2006).

Disconfirming theories is another area where open science wants to develop more capacity, rigor, and cultural force. Today, hobbled by a publishing industry attuned to printing only the latest discoveries, theories may linger without examination:

“Science is self-correcting (Merton 1942, 1973). If a claim is wrong, eventually new evidence will accumulate to show that it is wrong and scientific understanding of the phenomenon will change. This is part of the promise of science — following the evidence where it leads, even if it is counter to present beliefs. We do believe that self-correction occurs. Our problem is with the word ‘eventually.’ The myth of self-correction is recognition that once published, there is no systemic ethic of confirming or disconfirming the validity of an effect. False effects can remain for decades, slowly fading or continuing to inspire and influence new research…. Further, even when it becomes known that an effect is false, retraction of the original result is very rare…. Researchers who do not discover the corrective knowledge may continue to be influenced by the original, false result. We can agree that the truth will win eventually, but we are not content to wait” (Nosek et al. 2012).

The academy is also plagued with what David Graeber calls “bullshit jobs:” “Consider here some figures culled from Benjamin Ginsberg’s book The Fall of the Faculty (Oxford, 2011). In American universities from 1985 to 2005, the number of both students and faculty members went up by about half, the number of full-fledged administrative positions by 85 percent — and the number of administrative staff by 240 percent.…Support staff no longer mainly exist to support the faculty. In fact, not only are many of these newly created jobs in academic administration classic bullshit jobs, but it is the proliferation of these pointless jobs that is responsible for the bullshitization of real work…” (Graeber 2018; Accessed April 14, 2019).

Finally, there’s a whole layer of ersatz prestige that the academy has built up around what Cameron Neylon and others call “bullshit excellence;” “‘Excellence’” they remind us, “is not excellent, it is a pernicious and dangerous rhetoric that undermines the very foundations of good research and scholarship” (Moore et al. 2017).

All these sources of bullshit in the academy are why open science needs to be based on fierce equality. Fierce equality will prompt significant changes to how societies, universities, and funders view and support the science endeavor. Fierce equality militates against bullshit excellence and privilege in the academy, against the gamification of careers and reputations using external metrics, such as journal impact factors, and ultimately against all forms of the “Matthew effect” that amplifies inequality in funding and recognition. Fierce Equality — together with Demand Sharing — enables open scientists to pursue their passion for new knowledge freed from the conflicts of interest that postpone moral decisions and lead to bias and bad science.

Ways forward

Toxic culture practices are not integral to how your department, laboratory, school, college, university, agency, etc. operates. You can identify these and work to end them. This is where alternative, intentional cultural practices are essential. As an open-science culture change agent, you can help grow a new organizational infraculture to dis-place and re-place toxified practices. It takes work to maintain a non-toxic organizational culture; but a lot more work to fix one that has become toxic. How do you keep your organizational culture positive, transparent, and democratic?

“The most hidebound, bureaucratic, lumbering, terrible organization got each one of its unreasonable policies one drip at a time. Taken individually, each layer of stupid rules was almost weightless, but in quantity, they’re a smothering weight.” (Cory Doctorow (2014); Accessed June 25, 2020).

Learning from Silicon Valley

The practical advantages of stewarding your organization’s culture so that this does not drift into toxic shallows are now topics of hundreds of start-up organizational guiding books, articles, blogs, conferences, and consultant efforts. CEOs are routinely coached about the necessity of “not fucking up your culture,” (2014 blog by Brian Chesky, CEO of AirBnB; Accessed October 5, 2020). An equal number of guides outline what people generally know: how to recognize when your organization’s culture has gone sour. You can Google up “what does toxic culture mean” and get a couple hundred million pieces of advice. A lot of the conditions that are described as toxic at the organizational level resonate with behaviors that are attributed to assholes at the individual level.

Institutional guilt

One major example of toxic management practices are institutional rules that everyone knows, but few follow. This situation leads to “institutional guilt.” You are still guilty for not following a rule that nobody follows.

Institutional guilt happens when values and vision, and policies and processes are routinely broken. The routine creates an alternative policy, a counter-value, which becomes the operational norm for the organization. As this new policy and its values cannot be spoken of, it is almost impervious to change. The “real rule” is unspoken, detached from official management practices, and cemented into everyday interactions at the organization.

In a mostly volunteer organization, like a learned society, or an online network, this situation will lead to almost certain failure; volunteers will flee, staff will be disengaged. In a university department or school, employees will look for lateral transfers to less stressful units. Those that remain may do so for suspect reasons. Bullies and jerks take advantage of institutional guilt by creating a show of following the written rules and threatening those who don’t.

Institutional guilt grows from a routinized violation of your organization’s stated values, vision, rules, or policies. When enough people violate a rule without effects, the rule does not just go away. The rule becomes weaponizable as a tool to arbitrarily punish individuals. Institutional guilt is symptomatic of dysfunctional communication strategies inside an organization. It leads to distrust of staff and disengagement from the organization’s vision. Staff and volunteer disengagement/disenchantment is a prime reason organizations fail (Duckles et al. 2005). Your university needs to escape this all-too common vortex of toxic behaviors. Institutional guilt is something that will ruin your academy institution or online organization. It poisons the culture and it drives away volunteers while it demoralizes your staff.

The routines that include institutional guilt are a subset of what Rice and Cooper (2010) call “unusual routines.” These are dysfunctional outcomes, mostly of flawed communication practices. There is no organizational structure that can prevent these entirely. There are cultural practices available to repair unusual routines. The notion that toxic culture fosters jerks is only a part of the dynamic. The emboldened assholes do their part to add more toxicity over time. One of the remedies for toxic culture is to marginalize those jerks who are a) unrepentant, and b) un-fireable (e.g., assholes with tenure).

In the process of introducing the virtues and values of open science, you might and should look to see how these dis-empower jerkish tactics in your team, department, or laboratory. As opportunities and incentives bad behavior diminish, you might discover that colleagues who behaved badly in the past — perhaps including you, on occasion (getting a PhD opens up a lot of doors for bad behavior) — no longer feel like they have the need to be unkind to one another. Change the culture and you might also help others internalize the new virtues your culture promotes.

Toxic cultural practices will murder your academic dreams

Let’s recap here:

1. Hyper-competition feeds self-interested behaviors and can lead to sadism, or, more commonly, to efforts at manipulation (faking data, taking credit, undermining the efforts of others), and harassment of junior colleagues. Other people become obstacles. They exist to be defeated/demeaned or to become instruments to use in the process of “winning.”

2. Sexual harassment and intellectual bullying feeds spitefulness in those who survive this, and who later find themselves in a position to bully others. Spitefulness also infects the peer-review process for publication, employment, career advancement, and research funding.

3. Bullshit prestige and the Matthew Effect feed entitlement, narcissism, and egoism among those in career positions that have benefitted from the process of cumulative advantage. They use their advantaged position to promote more bullshit prestige.

4. The neo-liberal market logic feeds moral disengagement, delaying moral decisions in favor of expedience and advantage. Cheating on research results to gain publication harms the entire academy.

5. Organizational culture decays from neglect and the intentions of bad actors within. Institutional guilt replaces transparency and silences conflict. Workplaces become fearful and employees unproductive and unhappy. There’s a whole other blog here about how the day-to-day emotional work of navigating these toxic workplaces gets offloaded to assistants and low-paid staff, often women.

Your organization can govern its way out of any toxic culture

There are some roads that lead away from toxic practices in the academy. One of them is through new governance practices. Sometimes toxic practices get burned into the everyday life of an organization. Implementing corrective governance is a good way to build in protection against institutional guilt. You also need to be sure that your employees and volunteer committees do not fall into the trap of violating your own values and policies for some immediate purpose. Better governance opens up learning capabilities and communication channels to help limit and repair occasions where volunteers or staff do stray from your organization’s vision and values.

The next section of the Handbook will take you through the process of refactoring your organization using a form of “double-loop” governance. This is one way forward. There are others you can try. The point is, you are not trapped in a toxic culture, run by assholes who get to decide your professional life for you, or the front path for science.

Remember that decisions that don’t get made by the people who are supposed to make them get made anyhow by the people who need them. Even the decision not to decide today is made by someone. When decisions are guided by the values and vision of the organization, when the process is transparent, when the conflicts appear on the surface, when failure is just another chance at success, and when leadership opens up in front of those who have proven their worth: that is when institutional guilt has no purchase on the logic of your organization.

References

Duckles, Beth M., Mark A. Hager, and and Joseph Galaskiewicz. 2005. “How Nonprofits Close: Using Narratives to Study Organizational Processes.” In Qualitative Organizational Research: Best Papers from the Davis Conference on Qualitative Research, edited by Kimberly D. Elsbach, 169–203. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Feinberg, M., R. Willer, J. Stellar, and D. Keltner. 2012. “The Virtues of Gossip: Reputational Information Sharing as Prosocial Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102 (5): 1015.

Feist, Gregory J. 2006. The Psychology of Science and the Origins of the Scientific Mind. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. 2019. Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Frankfurt, Harry G. 2009. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press.

Ginsberg, Benjamin. 2011. The Fall of the Faculty. Oxford University Press.

Grant, Adam M. 2013. Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success. New York, N.Y: Viking.

Merton, Robert K. 1942. “Science and Technology in a Democratic Order.” Journal of Legal and Political Sociology 1 (1): 115–126.

— — — . 1973. The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations. University of Chicago press.

Moore, S., C. Neylon, M.P. Eve, D.P. O’Donnell, and D Pattinson. 2017. “‘Excellence R Us’: University Research and the Fetishisation of Excellence.” Palgrave Communications 3: 16105.

Nosek, Brian A, Jeffrey R Spies, and Matt Motyl. 2012. “Scientific Utopia: II. Restructuring Incentives and Practices to Promote Truth over Publishability.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 7 (6): 615–631.

Rice, Ronald E, and Stephen D Cooper. 2010. Organizations and Unusual Routines: A Systems Analysis of Dysfunctional Feedback Processes. Cambridge University Press.

Schulz, Kathryn. 2011. Being wrong: Adventures in the margin of error. Granta Books.